How has Canadian political science evolved since 1968, the first year that the Canadian Journal of Political Science was published in its “modern” format? One possible way to answer this question is to look at what people have been talking about in CJPS and who they have been talking with.

Before going further, I want to point out that the following was inspired by similar projects in philosophy done by Kieran Healy and in sociology done by Neal Caren. The basic idea is the same as theirs— and the move from raw data to network data is a direct copy of Caren’s python script— but the goal is somewhat different.

The Basic Idea

Let’s assume that what is published in CJPS is what Canadian political science is talking about and that who these articles cite is a reflection of the debates that are happening. Let’s also assume that papers (books or articles) that are often cited together are addressing the same issue, that they are part of the same discussion. Looking at how these co-citation networks evolved through time could help shed light on the evolution of Canadian political science.

Methods and Data

I start with all the articles that have been published in CJPS from 1968 to 2017. According to Web of Science, that brings the total to 1457 articles. Using WofS, I then downloaded the list of references from all these articles. These references can be books, articles, what have you. In total, there were around 56000 citations. Of course many of the cited items are there multiple time. Using Carens’s python script, I then created a dataset containing all the sources that were cited by these articles as well as connections between each of them.

In order to be able to see anything out of these network graphs, I had to set some limits. To be part of the network — to be represented by a node — an item had to be cited at least five times during the period examined. To be linked to another item — for an edge to be represented in the network —items had to be cited together at least three times. Changing these parameters changes the networks to some extent, but after looking at multiple iterations, those are the ones that yield enough information to be meaningful while still being readable (although not always super readable).

The python code uses a community detection algorithm to form communities. The different colors you will see in the networks come from that algorithm, not from me. We can then try to make sense of the communities inductively. That is relatively straightforward in some cases but more difficult in others.

The Networks

To look at the evolution of the field, I decided to divide the source material in three periods of about 15 years. These periods are somewhat arbitrary, yet I would argue that they also map onto what we could view as significant periods in Canadian political science. As perhaps an argument in favor of these periods, my somewhat arbitrary temporal divisions appear to have completely different network patterns that can be seen as logical steps in the formation of an academic field. Here they are.

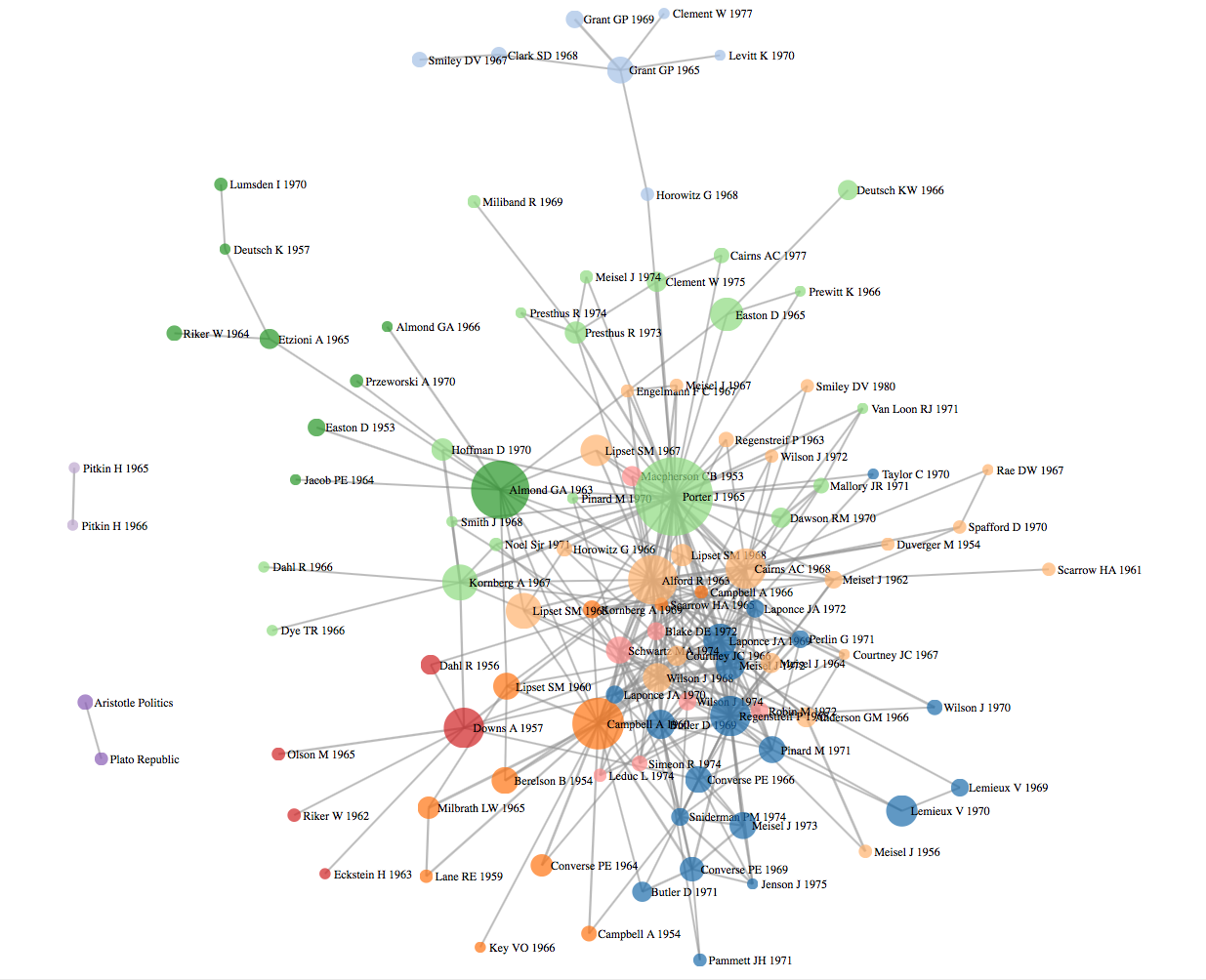

1968-1985: Getting Started

The first period starts with the first year CJPS was published and ends in 1985, right after the patriation and the constitutional debates that followed (I know it was in 1982…). Here’s what the co-citation network looks like.

You can zoom in if you want but the best way to make sense of it is to look at this dynamic version. To make it easier to read some of the sources, you can drag the nodes around. The interconnectedness can make this a bit clumsy but it can still be helpful I think.

Although the network is constituted by different communities, they are all linked together: everyone seems to be talking to everyone. The field has not yet specialized. In addition, many of the most important nodes are American sources, especially in the Elections and Public Opinion communities (Downs, Almond, Campbell, Alford). This makes sense. There were not many Canadian sources on these topics at that point. One notable exception is Regenstreif’s The Diefenbaker Interlude (1965).

Two more observations:

-

A total of four items are in French, all by Vincent Lemieux.

-

Porter’s The Vertical Mosaic is by far the most cited piece. It also serves as a link with Horowitz (1968) that connects what we could call the “Culture” community centered around Grant’s Lament of a Nation with everything else.

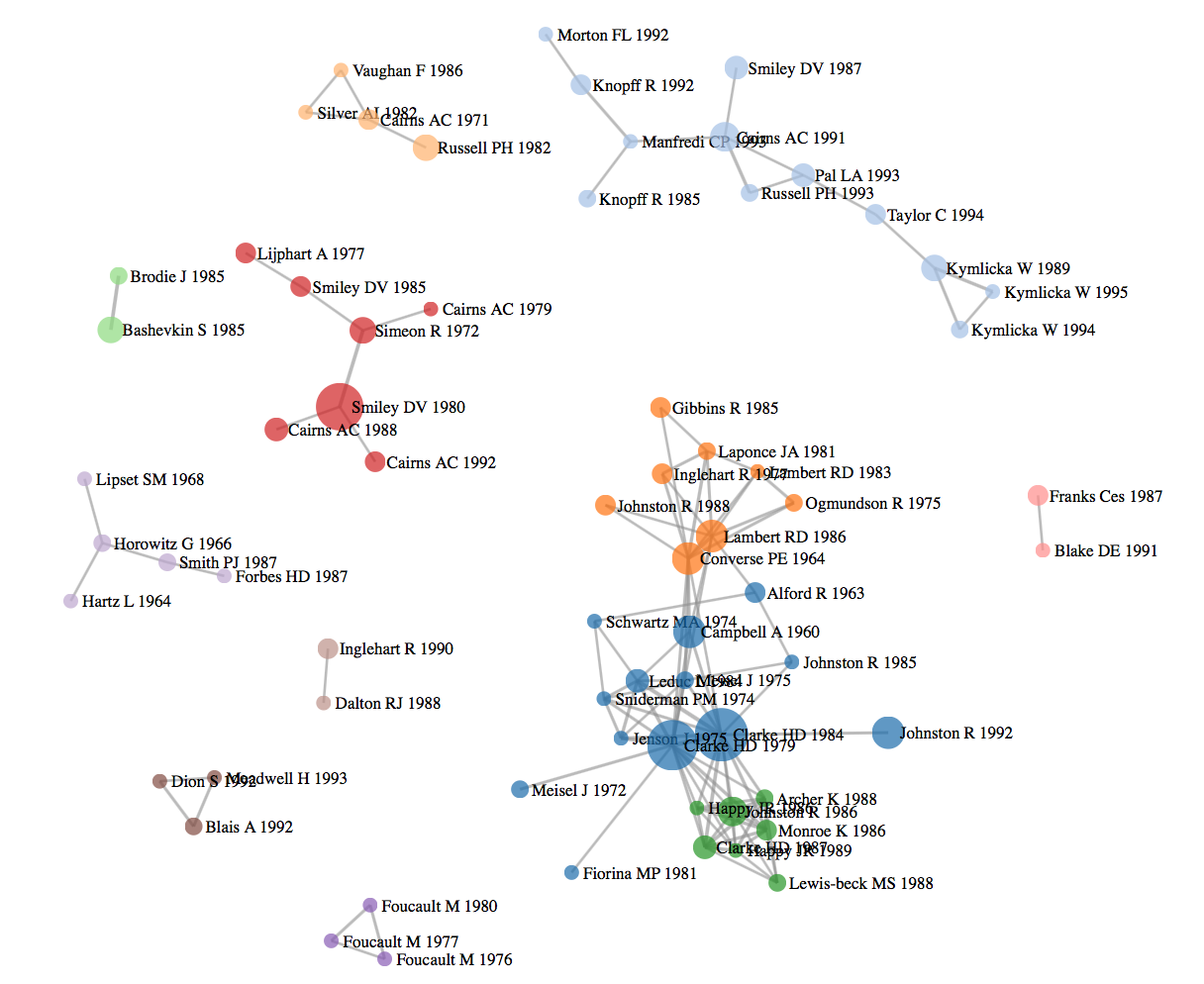

1985-2000: Specializing

The second period gives us a completely different picture. Rather than have a big “hairball” surrounded by smaller communities, we have several communities that are isolated from one another. The field is specializing. Connections between these communities will appear later.

Again, you can also look at a dynamic version.

So we have:

- A “Federalism” community (in red) around Smiley’s Canada in Question (1980).

- A “Culture” community in purple (is that purple?) with Hartz, Horowitz, and Lipset.

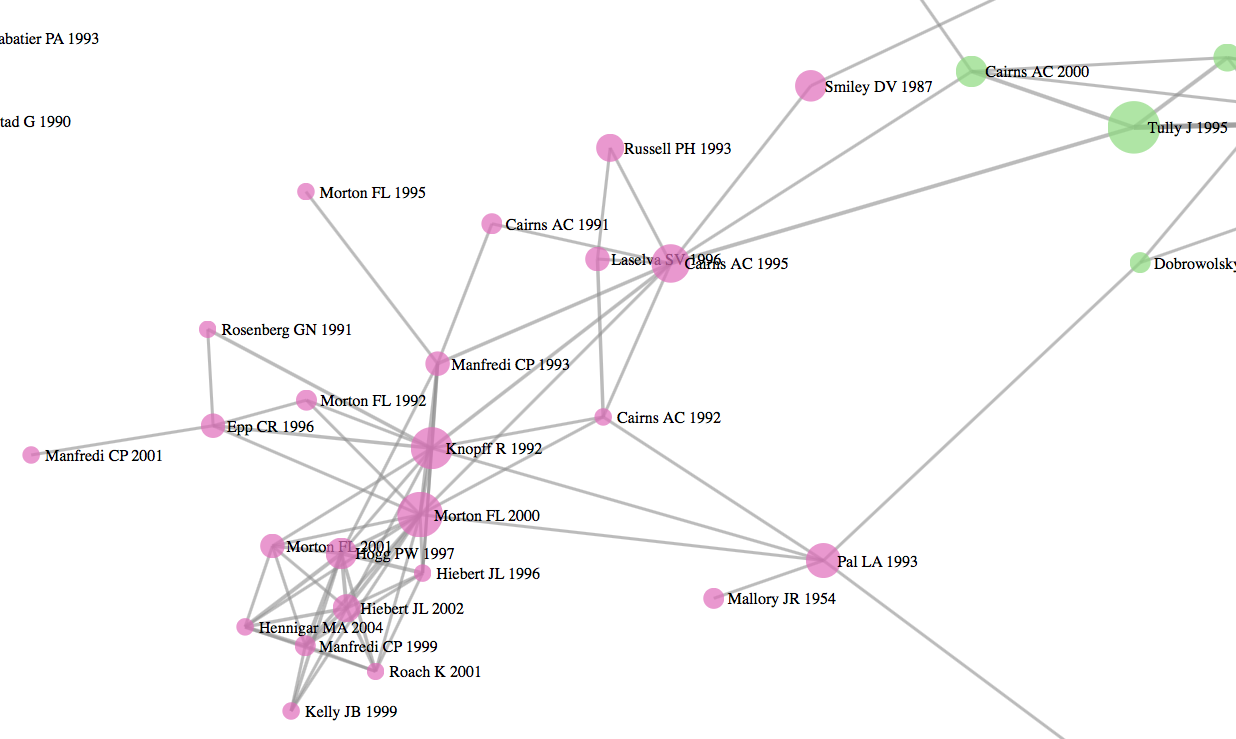

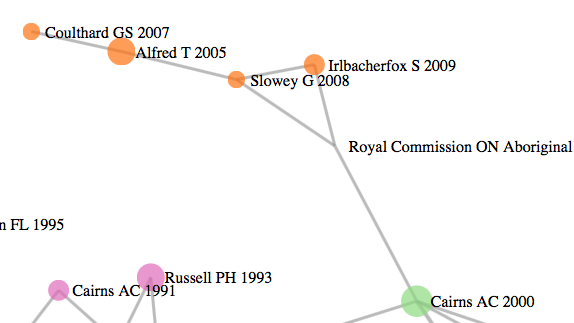

- A multiculturalism (writ large) community that also includes scholars who work on the courts. Cairns’s Disruptions: Constitutional Struggles from the Charter to Meech Lake” (1991) serves as the connection between the two, but the algorithm sees it as one community—something that will change in the next period.

- One small network that we could call “Elections and Public Opinion” but which contains three sub-communities. The main piece here is Clarke, Jenson, LeDuc, and Pammett’s Absent Mandate (1984). It’s unclear how the sub-communities differ or what sub-topics they are dealing with. One thing that’s notable is that Richard Johnston has a piece in each of those three sub-communities, including Letting the People Decide (1992) which is in the “outskirts” but will become more central in the next period.

- In terms of political theory that is not about Canada specifically, we went from a community comprised of Aristotle and Plato in the previous period, to a Michel Foucault trio that’s not linked to anything else. Signs of the time I guess.

- One striking difference is that many of the important items from the previous period did not make it into this one at all: Porter, Almond, Downs, and Regenstreif. Others now play smaller roles such as Alford.

- As far as I know, not a single node in the network is in French…well other than Foucault.

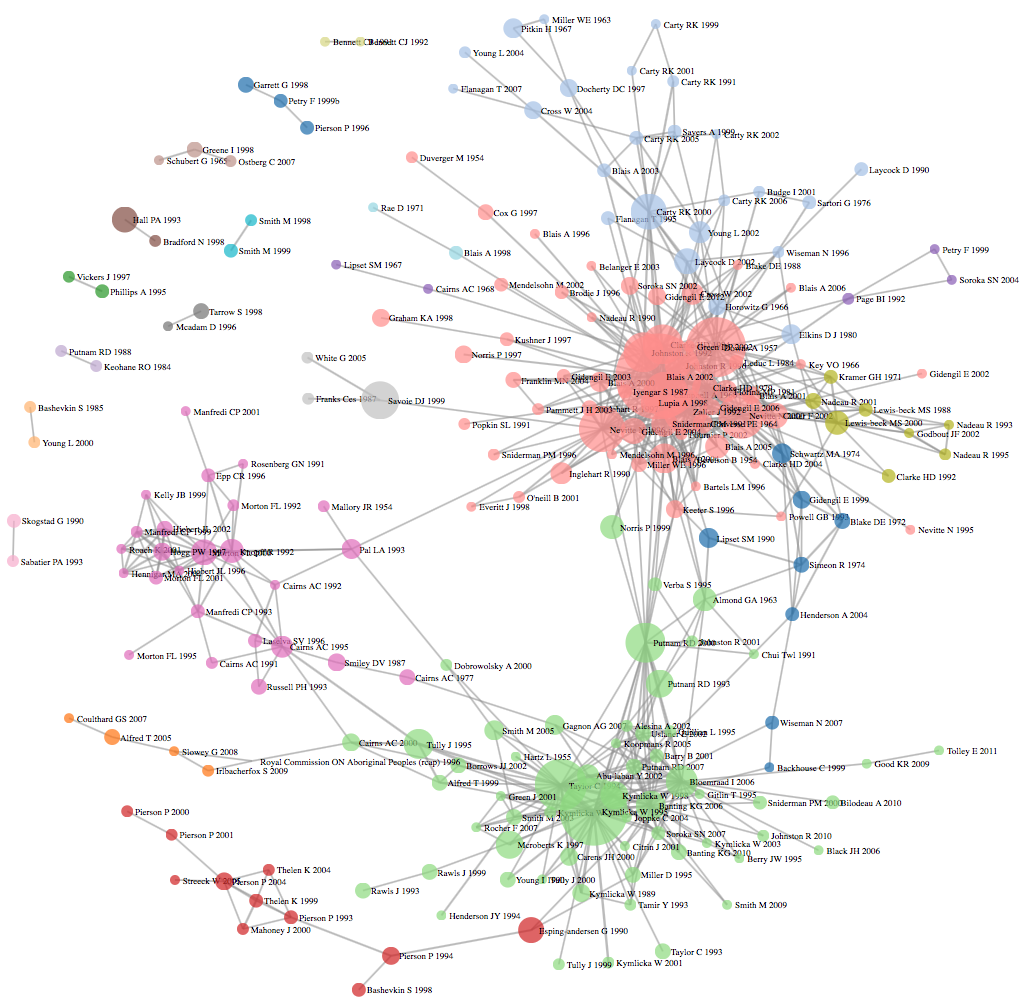

2000-2015: Expanding and Making Connections

The first thing that is striking with the third and last period is that there are many more citations and many more communities but that these numerous communities are all somewhat connected. They are not connected to the extent that it looks like the hairball we had in the first period, the communities are indeed distinct, but there are always one or two citations to act as bridges.

The still image above is not really useful so you can have a look at the dynamic version. Don’t be afraid to zoom in and drag stuff around.

Let’s have a look at some of these communities. After all, if we agree with our original assumption, this network can be seen as representing what Canadian political science is talking about now (well, not really, given the 5 citations threshold). For some of the still images below, I’ve played with the javascript so we can better see the nodes in each community.

Elections

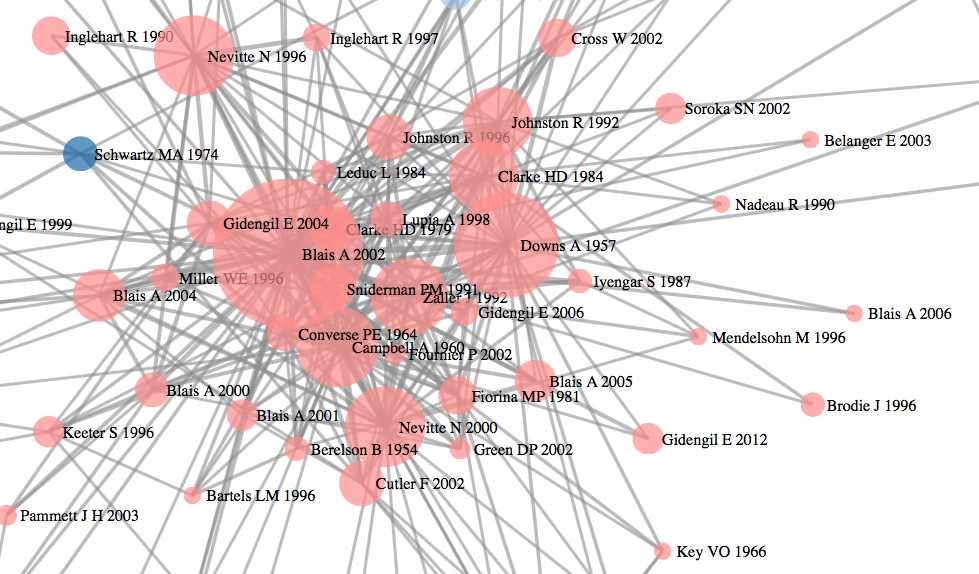

The most cited piece during that period is Blais et al.’s Anatomy of a Liberal Victory (2002) followed closely by Kymlicka’s Multicultural Citizenship (1995). These two books are at the center of the two main poles of the literature: Elections/Public opinion and Multiculturalism.

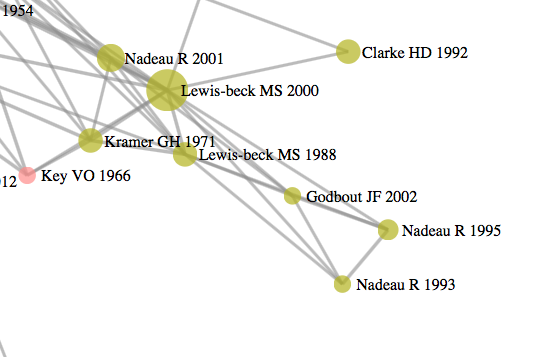

As was the case in the previous two periods, there are multiple sub-communities within what we can call the Elections community. Here’s the one that is more specifically about elections, with the Canadian Election Study — e.g. Johnston et al. (1992), Nevitte et al. (2000), Blais et al. (2002) — figuring prominently. Gidengil et al. (2012) is the most recent paper to pass the 5 citations threshold and make it into the network.

There is still some American sources in there but they are clearly not as fundamental as they were in the first period, with the exception of Downs’s Economic Theory of Democracy.

The study of Elections has itself specialized which gives us a little sub-community that I think is specifically about economic voting.

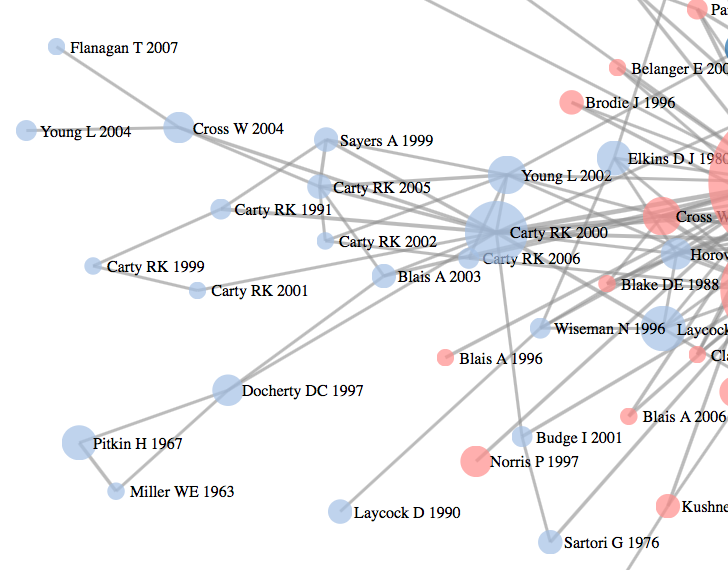

And one community that we could call the Carty community (he has 7 solo or co-authored items in this community), focusing on party politics.

I’m passing on some of the other small communities but please let me know if you think I am missing something of note.

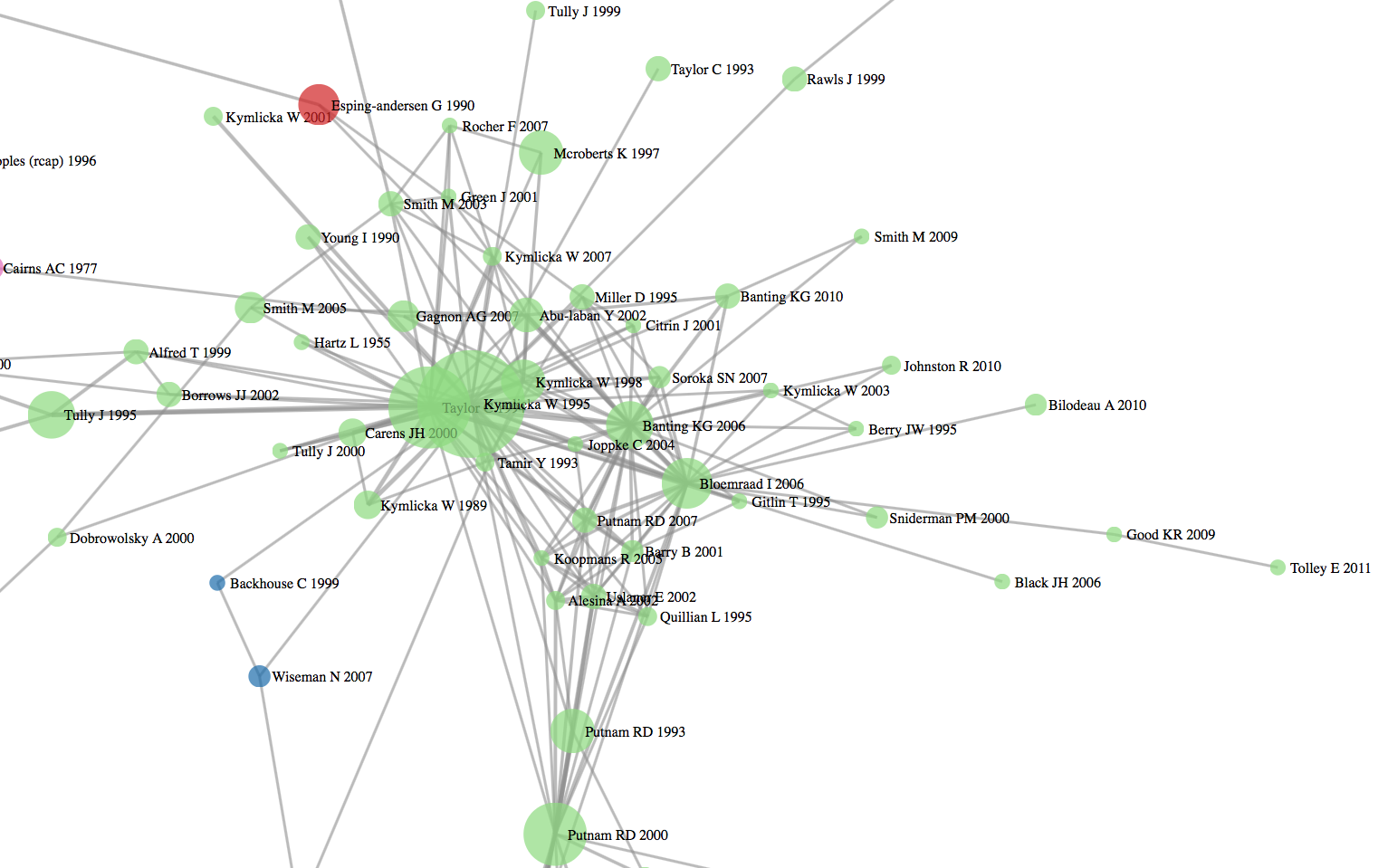

Multiculturalism and the Courts

Compared to the previous period, this community has now diversified and includes more empirical work such as Bowling Alone (Putnam 2000) and Becoming a Citizen (Bloemraad 2006). The Multiculturalism community links with the Institutionalism one through the connection between Esping-Anderson and Miller (1995) and Banting et al.(2006) - so the Welfare State discussion.

In the previous period, multiculturalism and the courts were part of a single community but not anymore. The Courts community now has enough connections among itself to be considered a community by the algorithm.

From the junction of these two literatures, a little community of scholars working more specifically on Indigenous issues emerged.

Other observations:

-

As I mentioned earlier, there’s a new “Institutionalism” community that is mostly American and centered around Paul Pierson and Kathleen Thelen. That community’s only link with the rest of the network is through Esping-Anderson.

-

Political theory is now completely subsumed under the multiculturalism community. Whereas we had “free standing” theory communities in previous periods (Ancient Greece in the 1st, Foucault in the 2nd), there is nothing similar in this last period.

Final thoughts

- Based on this method, one could conclude that political theory other than that linked to multiculturalism has never played a central role in Canadian political science.

- Another absent, perhaps unsurprisingly, is International Relations. Aside from a small Keohane-Putnam dyad in the last period, there’s nothing.

- Finally, this is obviously just one way to answer the question at the origin of this post: What is Canadian Political Science talking about (or what did it talk about in the past)? It is limited by our starting assumption — that to answer this question one can look at what articles published in CJPS are citing. The networks are also directly influenced by my periodization and by my limits on citations and connections, so it should still be taken as a partial answer.

A note on data

Although I spent some time cleaning the data, it is possible that some errors remain. It was - and still is - really messy. Here’s the raw data if you want to have a look at it. As you will see, sources are sometimes written in different formats. Some authors had their names spelled different ways, had their middle initial included in some instances but not in others, etc. I’ve tried to standardize it for the main sources, but I might have forgotten some. WoS also returned a lot of sources as “anonymous” so I had to figure out what they were exactly. Again, I might have missed a few. If you find mistake, please let me know. I’ll make sure to acknowledge your contribution here!